Tirotrofina u Hormona Estimulante de la Tiroides (TSH)

Liliana M. Bergoglio, Bioquímica Endocrinóloga, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina.

E-mail: liberg@uolsinectis.com.ar

Jorge H. Mestman, Médico Endocrinólogo, Universidad del Sur de California, Los Ángeles, CA, Estados Unidos NACB: Guía de Consenso para el Diagnóstico y Seguimiento de la Enfermedad Tiroidea

Fuente: Revista Argentina de Endocrinología y Metabilismo, Vol 42,N° 2, Año 2005.

Mencionamos con reconocimiento los nombres de los profesionales que participaron en la revisión de la traducción del documentooriginal sobre el cual está basada esta monografía:

Claudio Aranda, Hospital Carlos C. Durand, Buenos Aires, ArgentinaAldo H. Coleoni, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba,Argentina

N. Liliana F. de Muñoz, Hospital de Niños de la Santísima Trinidad,Córdoba, Argentina; Silvia Gutiérrez, Hospital Carlos C. Durand, Buenos Aires, Argentina

H. Rubén Harach, Hospital Dr. A.Oñativia, Salta, Argentina.

Durante más de veinticinco años los métodos para la determinación de TSH han sido capaces de detectar los aumentos de esta hormona característicos del hipotiroidismo primario. Sin embargo, los métodos modernos más sensibles, también posibilitan la detección de valores bajos de TSH típicos del hipertiroidismo. Estos nuevos métodos son ensayos inmunométricos no isotópicos (IMA), disponibles para una variedad de autoanalizadores para inmunoensayos. La mayoría de los métodos actuales está en condiciones de alcanzar una sensibilidad funcional de 0,02mUI/L o menor, necesaria para la detección de todo el rango de valores de TSH comprendidos entre el hipo y el hipertiroidismo. Esta sensibilidad permite distinguir entre una TSH francamente suprimida típica de la tirotoxicosis severa de Graves (TSH < 0,01 mUI/L) y los grados menores de supresión (TSH 0,01 – 0,1 mUI/L) que se observan en el hipertiroidismo leve y en ciertos pacientes con enfermedades no tiroideas (NTI).

En la última década, la estrategia diagnóstica para el uso de las determinaciones de TSH ha cambiado como resultado de los avances en la sensibilidad de los métodos. En la actualidad, se reconoce que la determinación de TSH es más sensible que la de T4L para la detección tanto de hipo como del hipertiroidismo.

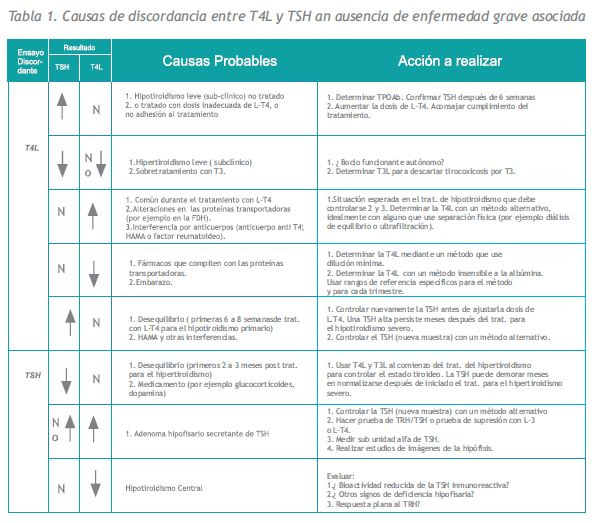

En consecuencia, algunos países promueven la determinación de TSH como estrategia primaria para el diagnóstico de la disfunción tiroidea en pacientes ambulatorios (siempre que el método de determinación tenga una sensibilidad funcional < o = 0,02 mUI/L). Otros países, prefieren aún la combinación de TSH + T4L, ya que la determinación de TSH como estrategia primaria no siempre detecta a los pacientes con hipotiroidismo central ni los tumores hipofisarios secretantes de TSH (19 y 195-197). Otra desventaja de la estrategia basada en la determinación de TSH es que la relación TSHT4L no se puede utilizar como “parámetro de validación clínica” para detectar interferencias o condiciones poco habituales caracterizadas por discordancias en dicha relación (Tabla 1).

1. Especificidad

(a) Heterogeneidad de la TSH

La TSH es una molécula heterogénea con diferentes isoformas que circulan en sangre y que están presentes en los extractos hipofisarios utilizados para la estandarización de los ensayos (Medical Research Council (MRC) 80/558). En el futuro, las preparaciones de TSH humana recombinante (rhTSH) se podrían utilizar como estándares primarios para los inmunoensayos de TSH (198). Los métodos TSH IMA actuales utilizan anticuerpos monoclonales que eliminan virtualmente la reactividad cruzada con otras hormonas glucoproteicas. Estos métodos, sin embargo, pueden detectar epitopes de isoformas anormales de TSH secretadas por algunos individuos eutiroideos, así como por algunos pacientes con patologías hipofisarias. Por ejemplo, los pacientes con hipotiroidismo central provocado por disfunción hipofisaria o hipotalámica, secretan isoformas de TSH con glucosilación anormal y reducida actividad biológica. La mayoría de los métodos, paradójicamente miden estas isoformas de TSH como normales o incluso elevadas (195, 197, 199). Asimismo, es posible observar niveles paradójicamente normales de TSH en pacientes con hipertiroidismo debido a tumores hipofisarios, secretan isoformas de TSH con aumento de la actividad biológica (196, 200, 201).

| Recomendación Nº 18. Investigación de valores discordantes de TSH sérica en pacientes ambulatorios |

| Un resultado de TSH discordante en un paciente ambulatorio con estado tiroideo estable, puede deberse a un error técnico. La pérdida de especificidad puede ser el resultado de un error de laboratorio, de sustancias interferentes (por ejemplo anticuerpos heterófilos) o la presencia de una isoforma inusual de TSH (ver Recomendación Nº 7 y Tabla 1). Los médicos pueden solicitar que su laboratorio realice las siguientes comprobaciones:*Confirmar la identidad de la muestra (por ejemplo que el laboratorio verifique si se ha cambiado una muestra de posición en la corrida). *Cuando la TSH es inesperadamente alta solicitar al laboratorio que vuelva a medir la muestra diluida, preferentemente en suero tirotóxico, para confirmar paralelismo. *Solicitar que el laboratorio analice la muestra con un método de otro fabricante (enviarla a otro laboratorio si fuera necesario). Es posible que haya un interferente si la variabilidad entre métodos para la misma muestra es > 50%. *Las verificaciones biológicas pueden ser útiles una vez que se hayan descartado los problemas técnicos.- Realizar una prueba de TRH para investigar un resultado bajo discordante de TSH, y esperar un incremento de dos veces (?4 mUI/L) en la respuesta en individuos normales. – Realizar una prueba con supresión de hormona tiroidea para verificar un valor alto discrepante de TSH. La respuesta normal a 1mg de L-T4 o 200?g de L-T3 administrados por vía oral es una supresión de la TSH de más del 90% a las 48 horas. |

(b) Probelmas técnicos

Los problemas durante el desarrollo de la técnica, como los pasos de lavados mal realizados, pueden dar resultados falsamente elevados de TSH (202). Además, cualquier sustancia interferente en la muestra (por ejemplo, los anticuerpos heterófilos HAMA) que produzca un ruido de fondo elevado o un falso puente entre los anticuerpos de captura y de señal creará una señal alta en el soporte sólido que se interpretará como un resultado falsamente elevado (203, 202).

(c) Métodos para detectar interferencia en un resultado de TSH

El método convencional de laboratorio para verificar la concentración de un analito, como la dilución, no siempre detecta un problema de interferencia. Como los métodos varían en su susceptibilidad hacia la mayoría de las sustancias interferentes, el modo más práctico de evaluarla es medir la concentración de TSH en la muestra utilizando un método de otro fabricante y comprobar si hay una discordancia significativa entre los valores. Cuando la variabilidad de las determinaciones de TSH en la misma muestra con métodos diferentes supera los valores esperados (>50% de diferencia), es posible que haya interferencia. Los controles biológicos también pueden resultar útiles para verificar un resultado inesperado. Los valores inapropiadamente bajos de TSH se pueden verificar con una prueba de estimulación de TRH (200ug I.V), el cual se espera que eleve la TSH a más del doble (incremento > o = 4 mUI/L) en individuos normales (204). En los casos de TSH inapropiadamente elevada, se esperaría que una prueba de supresión con hormona tiroidea (1mg L-T4 o 200ug L-T3, por vía oral) suprima la TSH enmás de un 90% a las 48 horas en individuos normales.

2. Sensibilidad

Históricamente, la “calidad” de un método para determinar TSH se ha establecido a partir de un patrón clínico: la capacidad del ensayo para discriminar niveles eutiroideos (~ 0,4 a 4,0 mUI/L) de concentraciones extremadamente bajas (menores a 0,01mUI/L) típicas e la «tirotoxicosis» de Graves. La mayoría de los métodos de TSH declaran un límite de detección de 0,02 mUI/L o menos (ensayos de «tercera generación»). (202)

Casi todos los fabricantes han abandonado el uso del parámetro “sensibilidad analítica” para expresar la sensibilidad de un ensayo de TSH,que se calcula a partir de la precisión intraensayo del calibrador cero, porque no refleja la sensibilidad del método en la práctica clínica (126, 127). Como alternativa se ha adoptado el parámetro “sensibilidad funcional” (202) que se calcula a partir del coeficiente de variación (CV) interensayo del 20% para el método y que se utiliza para establecer el valor mínimo que se puede informar para esa determinación (202).

| Recomendación Nº 19. Definición de sensibilidad funcional |

| La sensibilidad funcional debería usarse para determinar el límite de detección más bajo del ensayo. La sensibilidad funcional del ensayo de TSH se define como la concentración que puede ser determinada con un coeficiente de variación (CV) interensayo del 20% determinada con el protocolo. |

| Recomendación Nº 20. Protocolo para obtener la sensibilidad funcional de TSH y el perfil de precisión |

| Medir la TSH en mezclas s de suero humano que cubran el rango del ensayo en por lo menos 10 corridas diferentes. El valor de la mezcla más baja debería estar un 10% por encima del límite de detección y el valor de la mezcla más alta debería estar un 90% por sobre el límite superior del ensayo.*El fenómeno de «arrastre» se debería evaluar analizando primero la mezcla más alta seguida de la más baja. *Utilizar el mismo modo de prueba que para las muestras de pacientes (por ejemplo, simplificado o duplicado)*El operador debería desconocer la presencia de mezclas de sueros de prueba en la corrida. *Las corridas se deberían distribuir en un intervalo clínicamente representativo (por ejemplo 6 a 8 semanas para TSH en pacientes ambulatorios). Utilizar por lo menos dos lotes diferentes de reactivos y dos calibraciones distintas del instrumento durante el período de prueba. *Cuando se corra el mismo ensayo en dos instrumentos similares, periódicamente se deberían correr duplicados ciegos en cada instrumento para verificar la correlación. |

La sensibilidad funcional se debería determinar con un estricto seguimiento del protocolo recomendado que se diseña para evaluar el límite de detección de un ensayo en la práctica clínica (Recomendación N°20) y garantizar que el parámetro realmente represente el mínimo valor del ensayo que se puede informar de manera confiable. El protocolo está diseñado para tener en cuenta la variedad de factores que pueden influir en la imprecisión del método de TSH. Estos incluyen:

- Diferencias en la matriz entre el suero del paciente y el diluyente de los calibradores

- Disminución de la precisión con el tiempo

- Variabilidad entre los diferentes lotes de reactivos provistos por el fabricante

- Diferencias entre las calibraciones de los instrumentos y los operadores técnicos

- Arrastre desde las concentraciones altas hacia las bajas (205)

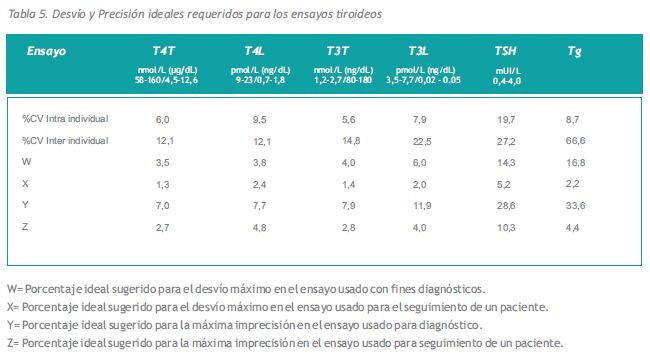

El uso de la sensibilidad funcional como límite de detección es un enfoque conservador para garantizar que cualquier resultado de TSH informado no sea simplemente “ruido” del ensayo. Además, el coeficiente de variación del 20 % entre corridas se aproxima a la máxima imprecisión requerida para los ensayos usados con fines diagnósticos (Tabla 5).

3. Intervalos de referencia de TSH

A pesar de las diferencias en los niveles de TSH relacionadas con el género, la edad y la etnicidad que reveló la encuesta NHANES III US recientemente publicada, no se considera necesario ajustar el intervalo de referencia para estos factores en la práctica clínica (18).

Los niveles de TSH sérica muestran una variación diurna con respecto al pico que se produce durante la noche y el nadir, que se aproxima al 50% del valor máximo y ocurre entre las horas 10:00 y 16:00 (123, 124). Esta variación biológica no influye en la interpretación del resultado ya que la mayoría de las determinaciones de TSH se realizan en pacientes ambulatorios entre las horas 08:00 y 18:00 y los intervalos de referencia de TSH se establecen para las muestras recolectadas durante ese mismo lapso. Los intervalos de referencia de TSH se deberían establecer utilizando muestras de individuos con TPOAb negativos, ambulatorios, eutiroideos, sin antecedentes personales ni familiares de disfunción tiroidea, ni bocio visible. La variación en los intervalos de referencia para los distintos métodos refleja las diferencias en el reconocimiento del epitope de las diferentes isoformas de TSH por los componentes del equipo de reactivos, y en el rigor aplicado a la selección de individuos normales.

| Recomendación Nº 21. Para laboratorios que realizan ensayos de TSH |

| La sensibilidad funcional es el criterio de calidad más importante que debe influir en la selección de un método para la determinación de TSH. Los factores prácticos como el instrumental, el tiempo de incubación, el costo y el soporte técnico, si bien importantes, son consideraciones secundarias. Los laboratorios deberían utilizar intervalos de calibración que optimicen la sensibilidad funcional, incluso si la re-calibración se debe realizar con mayor frecuencia que la recomendada por el fabricante:*Seleccionar un método para TSH que tenga una sensibilidad funcional ? 0,02 mUI/L. *Establecer la sensibilidad funcional independientemente del fabricante utilizando la Recomendación Nº 20. *No hay justificación científica para realizar el ensayo con un método menos sensible y luego si es necesario, con uno más sensible. (La menor sensibilidad genera valores falsamente elevados no falsamente bajos). |

Las concentraciones de TSH determinadas en sujetos eutiroideos normales se desvían con una “cola” relativamente larga hacia los valores más altos de la distribución. La distribución de los valores se vuelve más normal cuando se los transforma logarítmicamente. Para los cálculos del rango de referencia, es común la transformación logarítmica de los resultados de TSH, para calcular el intervalo de referencia del 95% (valor de la media de la población típica ~1,5 mUI/L, rango entre 0,4 y 4,0 mUI/L en poblaciones sin deficiencia de yodo) (202, 206). Sin embargo, debido a la elevada prevalencia de hipotiroidismo leve (subclínico) en la población general, es probable que el límite superior actual del rango de referencia de la población sufra un sesgo por la inclusión de personas con disfunción tiroidea oculta (18).

(a) Límites superiores de referencia para la TSH

Durante las últimas dos décadas, el límite superior de referencia para la TSH ha disminuido constantemente de ~10 a aproximadamente ~4,0-4,5 mUI/L. Esta disminución refleja diversos factores que incluyen las mejoras en la sensibilidad y especificidad de los ensayos inmunométricos actuales basados en anticuerpos monoclonales, el reconocimiento de que los valores normales de TSH se distribuyen logarítmicamente y, en especial, las mejoras en la sensibilidad y especificidad de los ensayos de anticuerpos antitiroideos que se utilizan para la preselección de los individuos. El reciente estudio de seguimiento de la cohorte te de Whickham ha encontrado que los individuos con TSH sérica >2.0 mUI/L en su primera evaluación tenían una mayor probabilidad de desarrollar hipotiroidismo durante los próximos 20 años, en especial si sus anticuerpos antitiroideos eran elevados (35). También se observó un aumento en la probabilidad en sujetos con anticuerpos negativos. Es probable que esos individuos tuvieran niveles bajos de anticuerpos antitiroideos que no se pudieron detectar con los métodos insensibles de aglutinación de anticuerpos microsomales utilizados en el estudio inicial (207). Es posible también que incluso los inmunoensayos actuales sensibles de TPOAb no puedan identificar a todos los individuos con insuficiencia tiroidea oculta. Quizás en el futuro el límite superior del rango de referencia eutiroideo para la TSH sérica se reduzca a 2,5 mUI/L ya que >95% de los voluntarios normales eutiroideos sometidos a una rigurosa selección tienen valores de TSH sérica entre 0,4 y 2,5 mUI/L.

| Recomendación Nº 22. Intervalo de referencia para TSH |

| Los intervalos de referencia para TSH se deberían establecer a partir de los limites de confianza del 95% de los valores logarítmicamente transformados de por lo menos 120 individuos voluntarios normales eutiroideos seleccionados rigurosa y selectivamente que no presenten:*Autoanticuerpos tiroideos detectables, TPOAb o TgAb (determinados por inmunoensayos sensibles) *Antecedentes personales ni familiares de disfunción tiroidea *Bocio visible ni palpable *Medicamentos (excepto estrógenos) |

(b) Límites inferiores de referencia para TSH

Antes de la era de los ensayos inmunométricos, los métodos de determinación de TSH eran demasiado insensibles para detectar valores en el extremo inferior del rango de referencia (209). Sin embargo, los métodos actuales pueden medir TSH en el extremo inferior y situar los límites inferiores entre 0,2 y 0,4 mUI/L (202). Como la sensibilidad de los métodos ha mejorado, ha aumentado el interés por definir el verdadero límite inferior del rango normal para determinar con mayor precisión la presencia de hipertiroidismo leve (subclínico). Los estudios actuales sugieren que los valores de TSH en el rango entre 0,1 y 0,4 mUI/L pueden representar un exceso de hormona tiroidea y en los pacientes añosos podrían estar asociados con un aumento en el riesgo de fibrilación auricular y mortalidad cardiovascular (36, 37). Por lo tanto es importante excluir cuidadosamente a los individuos con bocio y cualquier enfermedad o estrés de la cohorte normal seleccionada para el estudio del rango de referencia.

4. Uso clínico de las determinaciones de TSH

(a) Búsqueda de disfunción tiroidea en pacientes ambulatorios

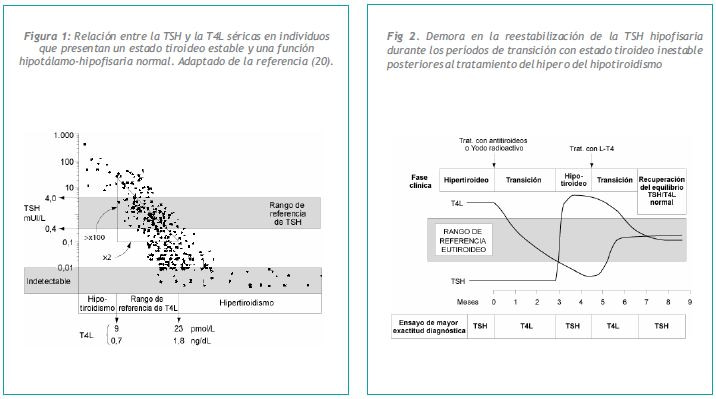

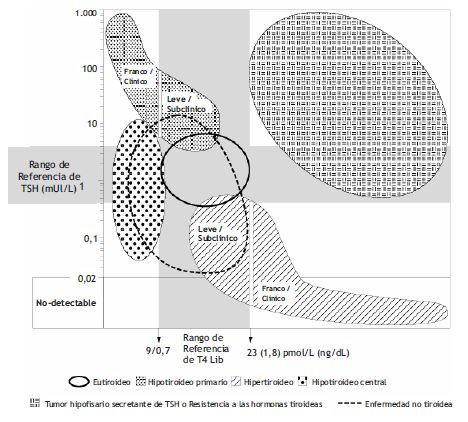

La mayoría de las sociedades profesionales recomienda que se utilice la TSH para determinar disfunción tiroidea en pacientes ambulatorios, siempre que el ensayo utilizado tenga una sensibilidad funcional igual o menor a 0,02 mUI/L (4, 10, 210). Determinar la sensibilidad del ensayo de TSH es fundamental para la detección confiable de valores por debajo de lo normal, ya que los ensayos menos sensibles tienden a producir resultados falsamente normales en muestras con concentraciones de TSH por debajo de lo normal (202). La relación logarítmica / lineal entre la TSH y la T4L determina que la TSH sérica sea el ensayo de elección, ya que sólo la TSH puede detectar grados leves de exceso o deficiencia de hormona tiroidea (Figura 1). La prevalencia de disfunción tiroidea leve (subclínica), caracterizada por una TSH anormal asociada a una T4L en el rango normal informada en estudios de población es de ~10% y 2%, para el hipo e hipertiroidismo subclínicos, respectivamente (10, 18, 25, 211). A pesar de la sensibilidad clínica de la TSH, una estrategia diagnóstica basada en TSH tiene dos limitaciones fundamentales. En primer lugar, requiere que la función hipotalámica hipofisaria sea normal. En segundo lugar, que el estado tiroideo del paciente sea estable, es decir que al paciente no se le haya administrado un tratamiento para el hipo ni el hipertiroidismo recientemente Figura 2 (19). Si alguno de estos dos criterios no se cumplen, los resultados de la TSH sérica pueden llevar a un diagnóstico confuso (Tabla1).

Cuando se investiga la causa de una TSH anormal en presencia de T4L y T3L normales, es importante reconocer que la TSH es una hormona lábil y sujeta a influencias hipofisarias no tiroideas (glucocorticoides, somatostatina, dopamina, etc.) que pueden alterar la relación TSH/T4L (69, 70, 71, 212). Es importante confirmar toda anormalidad de la TSH en una nueva muestra extraída después de ~3 semanas antes de hacer un diagnóstico de disfunción tiroidea leve (subclínica) como causa de una anormalidad aislada de la TSH. Después de confirmar una TSH alta, la determinación de TPOAb es útil para establecer la presencia de autoinmunidad tiroidea como causa de hipotiroidismo leve (subclínico). Cuanto mayor es la concentración de TPOAb, más rápido es el desarrollo de disfunción tiroidea. Después de confirmar una TSH baja puede ser difícil establecer inequívocamente un diagnóstico de hipertiroidismo leve (subclínico), especialmente si el paciente es añoso y no recibe tratamiento con L-T4 (34). En presencia de bocio multinodular, es probable que la autonomía tiroidea sea la causa de hipertiroidismo leve (subclínico) (213).

No hay consenso con respecto a la edad óptima para iniciar la investigación de disfunción tiroidea. Las recomendaciones de la American Thyroid Association sugieren comenzar a los 35 años y, a partir de ese momento, cada 5 años. (10). El análisis de decisión parece reforzar la relación costo/efectividad de esta estrategia, especialmente en mujeres (215). La estrategia de utilizar TSH para investigar hipo e hipertiroidismo leves (subclínicos), seguirá debatiéndose hasta que se logre un mayor acuerdo acerca de las consecuencias clínicas y el resultado de tener una TSH crónicamente anormal. Además, se necesita llegar a un acuerdo con respecto al nivel de anormalidad de TSH que indicaría la necesidad de tratamiento (216,217).

Cada vez más evidencia sugiere que los pacientes con una anormalidad persistente de TSH pueden estar expuestos a un mayor riesgo si no reciben tratamiento. Específicamente, un estudio reciente informó un aumento en el índice de mortalidad cardiovascular cuando los pacientes tenían una TSH sérica crónicamente baja (37). Además, un creciente número de informes indica que el hipotiroidismo leve en las primeras etapas del embarazo aumenta la pérdida fetal y daña el coeficiente intelectual del bebé (63-65). Estos estudios apoyan la eficacia de una evaluación temprana de la función tiroidea, especialmente en mujeres en edad fértil.

(b) Pacientes ancianos

La mayoría de los estudios apoyan la investigación de disfunción tiroidea en personas ancianas (10, 35, 214). La prevalencia tanto de TSH baja como alta (asociada con T4L normal) aumenta en los pacientes ancianos en comparación con los más jóvenes. A medida que se envejece, aumenta la prevalencia de tiroiditis de Hashimoto, asociada con elevación de TSH y TPOAb detectables (35). En los pacientes ancianos, también se produce un aumento en la incidencia de TSH baja (35). Una TSH baja puede ser transitoria, pero es un hallazgo persistente en aproximadamente el 2 % de los individuos ancianos, sin ninguna otra evidencia aparente de disfunción tiroidea (36, 214). Esto puede deberse a un cambio en el valor de ajuste con la T4L, un cambio en la bioactividad de la TSH, o un leve exceso de hormona tiroidea (218). Un estudio reciente realizado por Parle y colaboradores mostró un aumento en el índice de mortalidad cardiovascular en esos pacientes (37). Esto sugiere que la causa de un valor persistentemente bajo de TSH se debería investigar activamente (37). El bocio multinodular se debería descartar como causa en especial en zonas de deficiencia de yodo (213). Los medicamentos que ingiere el paciente, se deberían revisar cuidadosamente (incluidos los de venta libre, algunos de los cuales contienen T3). Si no hay presencia de bocio y los antecedentes de medicamentos son negativos, se recomienda volver a controlar la TSH sérica junto con TPOAb después de 4 a 6 semanas. Si la TSH aún se mantiene baja y los TPOAb son positivos, se debería considerar la posibilidad de una disfunción tiroidea autoinmune. El tratamiento ante una TSH baja se debería determinar según cada caso.

(c) Tratamiento de reemplazo con L-T4

En la actualidad existe amplia documentación que demuestra que los pacientes hipotiroideos tienen valores de T4L sérica en el tercio superior del intervalo de referencia cuando la dosis de reemplazo con L-T4 se ajusta para situar a la TSH dentro del rango del objetivo terapéutico (0,5-2,0 mUI/L) (219, 220).

La levotiroxina (L-T4), y no la tiroides disecada, es la medicación de reemplazo a largo plazo preferida para el hipotiroidismo.Generalmente, con una dosis promedio de L-T4 equivalente a 1,6 ug/kg de peso corporal/día en los adultos se logra un estado eutiroideo. Los niños necesitan dosis más elevadas (hasta 4,0 ug/kg de peso corporal/día) y los individuos ancianos dosis menores (1,0 ug/kg de peso corporal/día) (221, 222). La dosis inicial y el período de tiempo óptimo necesario para establecer la dosis total de reemplazo se deberían personalizar en función de la edad, el peso y el estado cardíaco del paciente. Se debe aumentar la dosis de L-T4 durante el embarazo y en mujeres post-menopáusicas que recién comienzan el tratamiento hormonal de reemplazo (223).

Un resultado de TSH sérica entre 0,5 y 2,0 mUI/L es generalmente considerado el objetivo terapéutico para una dosis de reemplazo estándar con L-T4 para el hipotiroidismo primario.

Una concentración de T4L sérica en el tercio superior del intervalo de referencia es el objetivo terapéutico del tratamiento de reemplazo con L-T4 cuando los pacientes tienen hipotiroidismo central debido a disfunción hipofisaria o hipotalámica.

| Recomendación Nº 23. Tratamiento de reemplazo con levotiroxina (L-T4) para el hipotiroidismo primario |

| *La levotiroxina (L-T4), no la tiroides disecada, es el medicamento preferido para el tratamiento de reemplazo a largo lazo en el hipotiroidismo. *Generalmente, se logra un estado eutiroideo en los adultos con una dosis promedio de L-T4 de 1,6 ?g/kg de peso corporal/día. La dosis inicial y el período de tiempo para alcanzar el reemplazo completo se debería personalizar en función de la edad, el peso y el estado cardíaco del paciente. Normalmente la dosis inicial de L-T4 es de 50-100 ?g diarios. La determinación de TSH sérica después de seis semanas indicará la necesidad de ajuste de dosis con aumentos de 25 a 50 ?g.*Los niños requieren dosis más elevadas de L-T4, hasta 4.0ug/kg de peso corporal/día, debido a la rapidez de su metabolismo. Los valores de TSH y de T4L se deberían evaluar utilizando rangos de referencia específicos para cada edad y método (Tabla 3). *Un nivel de TSH sérica entre 0,5 y 2,0 mUI/L, generalmente se considera el objetivo terapéutico óptimo para una dosis estándar de reemplazo con L-T4 para el hipotiroidismo primario. *La TSH demora en re-equilibrarse luego de una nueva dosis de tiroxina (Recomendación Nº 2). Se necesitan entre 6 a 8 semanas antes de volver a evaluar la TSH después de un cambio de dosis de L-T4 o de marca comercial. *La discontinuidad o la falta de cumplimiento con el tratamiento de reemplazo con levotiroxina (L-T4) resultará en valores discordantes de TSH y T4L (TSH elevada / T4L elevada) debido a la persistente inestabilidad del estado tiroideo (Recomendación Nº 2). Tanto la TSH como la T4L se deberían utilizar para controlar a dichos pacientes. *Los requerimientos de tiroxina disminuyen con la edad. Los individuos mayores quizás requieran menos de 1.0ug/kg de peso corporal/día y se los debe ajustar muy progresivamente. Se recomienda una dosis inicial de 25ug para los pacientes con evidencia de cardiopatía isquémica seguida de aumentos de 25ug en la dosis cada 3 a 4 semanas hasta que se alcance la dosis de reemplazo completa. Algunos médicos consideran que un valor más elevado de TSH (0,5-3,0 mUI/L) puede ser adecuado para los pacientes ancianos. *En casos de hipotiroidismo severo una dosis inicial mayor de L-T4 es el medio más rápido para restaurar el nivel terapéutico de T4L porque el exceso de sitios de fijación sin ocupar puede bloquear la respuesta de la T4L al tratamiento.*Los requerimientos de tiroxina aumentan durante el embarazo. El estado tiroideo se debe controlar con TSH + T4L en cada trimestre del embarazo. Se debería aumentar la dosis de L-T4 (generalmente 50ug/día) para mantener la TSH sérica entre 0,5 y 2,0 mUI/L y una T4L sérica en el tercio superior del intervalo normal de referencia. *Las mujeres post menopáusicas que comiencen un tratamiento de reemplazo pueden necesitar un aumento en la dosis de L-T4 para mantener la TSH sérica dentro del objetivo terapéutico. *Se recomienda una determinación anual de TSH en los pacientes que reciben una dosis estable de L-T4. El momento óptimo para realizar la determinación de TSH no está influido por el momento del día en que se ingiere la dosis de L-T4. *Idealmente se debería tomar la L-T4 antes de comer, a la misma hora y con por lo menos 4 horas de separación con otros medicamentos o vitaminas. La dosis nocturna debería tomarse dos horas después de la última comida. *Es posible que los pacientes que inicien tratamiento crónico con colestiramina, sulfato ferroso, carbonato de calcio, proteína de soja, sucralfato y antiácidos que contengan hidróxido de aluminio, que influyen en la absorción de L-T4 necesiten una dosis más elevada para mantener la TSH dentro del rango del objetivo terapéutico. *Es posible que los pacientes a quienes se administra rifampicina y anticonvulsivantes que influyen en el metabolismo de la L-T4 también necesiten un aumento en la dosis para mantener la TSH dentro del rango del objetivo terapéutico. |

El esquema habitual para aumentar la dosis gradualmente hasta llegar a la dosis de reemplazo completa consiste en administrar la L-T4 con incrementos de 25 ug cada 6 a 8 semanas hasta alcanzar la dosis objetivo (TSH sérica 0.5-2.0 mUI/L). Como se muestra en la Figura 2, la TSH es lenta para equilibrarse otra vez ante un nuevo nivel de tiroxina. Los pacientes con hipotiroidismo crónico grave pueden desarrollar hiperplasia tirotrófica hipofisaria que quizás simule un adenoma hipofisario, pero que se resuelve después de varios meses de tratamiento de reemplazo con L-T4 (224). Es posible que los pacientes a quienes se administra rifampicina y anticonvulsivantes que influyen en el metabolismo de la L-T4 también necesiten un aumento en la dosis para mantener la TSH dentro del rango del objetivo terapéutico.

Tanto la T4 libre como la TSH deberían utilizarse para el control de pacientes hipotiroideos con sospecha de discontinuidad o falta de cumplimiento con el tratamiento con L-T4. La asociación paradójica de T4L alta y TSH alta a menudo indica que puede haber problemas con el cumplimiento del tratamiento. Concretamente, la ingestión aguda de L-T4, que no se tomó cuando correspondía, realizada antes de una visita clínica elevará la T4L pero no normalizará la TSH sérica debido al efecto “demora en la respuesta” (Figura 2). Se necesitan por lo menos 6 semanas antes de volver a determinar la TSH después de un cambio en la dosis de L-T4 o en la marca comercial. Se recomienda una determinación de TSH anual en los pacientes que reciben una dosis estable de L-T4. El momento del día óptimo para determinar TSH no está afectado por la hora en que se ingiere la L-T4 (133). No obstante, cuando se utiliza T4L como estrategia de evaluación, la dosis diaria debería omitirse, ya que la T4L sérica aumenta significativamente (~13%) sobre el nivel basal, durante 9 horas después de la toma de la última dosis (225).

Idealmente se debería tomar la L-T4 antes de comer, a la misma hora y con por lo menos 4 horas de separación con otros medicamentos o vitaminas. Muchos medicamentos pueden alterar la absorción o el metabolismo de la T4 (en especial colestiramina, sulfato ferroso, proteína de soja, sucralfato, antiácidos que contengan hidróxido de aluminio, anticonvulsivantes o rifampicina) (4, 226).

| Recomendación Nº 24. Tratamiento supresivo con levotiroxina (L-T4) |

| *LA TSH sérica se considera un factor de crecimiento para el carcinoma diferenciado de tiroides (CDT). La dosis habitual de L-T4 utilizada para suprimir la TSH en los pacientes con CDT es 2,1?g/kg de peso corporal/día. *El nivel de TSH a alcanzar para el tratamiento supresivo con L-T4 para los pacientes con CDT se debería personalizar en función de la edad y del estado clínico (incluidos los factores cardíacos y el riesgo de recidiva de CDT). *Muchos médicos utilizan un valor objetivo de 0,05- 0,1 mUI/L de TSH sérica para los pacientes de bajo riesgo y de *Algunos médicos utilizan un objetivo terapéutico dentro de un rango bajo-normal para la TSH cuando los pacientes tienen niveles no detectables de Tg sérica y no han tenido recidiva entre 5 y 10 años después de la tiroidectomía. *Si la ingesta de yodo es insuficiente, el tratamiento de supresión con L-T4 rara vez es una estrategia de tratamiento eficaz para reducir la magnitud del bocio. *Con el tiempo, el bocio multinodular habitualmente desarrolla una autonomía caracterizada por un nivel de TSH subnormal. La TSH sérica se debería controlar antes de iniciar un tratamiento de supresión con L-T4 en esos pacientes. |

(d) Tratamiento de supresión con L-T4

La dosis de L-T4 destinada a suprimir los niveles de TSH sérica a valores subnormales se reserva habitualmente para los pacientes con carcinoma tiroideo bien diferenciado para los que la tirotrofina se considera un factor trófico (227). La eficacia del tratamiento supresivo con L-T4 se ha determinado a partir de estudios retrospectivos sin control que han aportado resultados conflictivos (228, 229).

Es importante personalizar el grado de supresión de la TSH considerando los factores del paciente, como: edad, cuadro clínico, incluidos los factores cardíacos y riesgo de recurrencia del carcinoma diferenciado de tiroides, contra los efectos potencialmente dañinos de un hipertiroidismo iatrogénico leve sobre el corazón y los huesos (36). Muchos médicos utilizan un valor entre 0,05-0,1 mUI/L de TSH para los pacientes de bajo riesgo y de Además, los pacientes con bocio nodular a menudo ya tienen la TSH suprimida como resultado de la autonomía tiroidea (213).

| Recomendación Nº 25. Determinación de TSH en pacientes hospitalizados |

| TSH + T4L o T4T es la combinación de ensayos más útil para detectar disfunción tiroidea en un paciente enfermo hospitalizado. *Es más adecuado utilizar un intervalo de referencia de TSH más amplio (0,05 a 10,0 mUI/L) en pacientes hospitalizados. Los niveles séricos de TSH pueden volverse transitoriamente subnormales en la fase aguda y volverse elevados en la fase de recuperación de una enfermedad. *Un valor de TSH entre 0,05 y 10,0 mUI/L generalmente concuerda con un estado eutiroideo, o solamente con una anormalidad tiroidea menor que se puede reevaluar después de que pase la enfermedad. (Esto solamente se aplica a los pacientes que no reciben medicamentos como dopamina que inhibe directamente la secreción hipofisaria de TSH). *Un nivel normal-bajo de TSH en presencia de T4T y T3T bajas puede reflejar hipotiroidismo central como resultado de una enfermedad prolongada. Si esta es una condición que requiere o no tratamiento inmediato, es un tema incierto y actualmente controvertido. *En caso de sospecha de disfunción tiroidea, se puede realizar una determinación de anticuerpos antiperoxidasa tiroidea (TPOAb) para diferenciar enfermedad tiroidea autoinmune de NTI. |

(e) Determinación de TSH sérica en pacientes hospitalizados con (NTI)

Aunque la mayoría de los pacientes hospitalizados con enfermedades no tiroideas tienen concentraciones normales de TSH sérica, es frecuente observar anormalidades transitorias en la TSH en el rango entre 0,02 y 20 mUI/L en ausencia de disfunción tiroidea (20, 87, 92, 93). Se ha sugerido que el uso de un rango de referencia más amplio (0,02 –10 mUI/L) mejoraría el valor predictivo positivo de las determinaciones de TSH para la evaluación de los pacientes enfermos hospitalizados (20, 92, 93, 231). La TSH se debería utilizar junto con un método de estimación de T4L (o T4T) para evaluar a los pacientes hospitalizados con síntomas clínicos o a los pacientes con antecedentes de disfunción tiroidea (Recomendaciones 6 y 25).

A veces la causa de la anormalidad de la TSH en un paciente hospitalizado es evidente, como en el caso de los que reciben tratamiento con dopamina o glucocorticoides (87, 92). En otros casos, esa anormalidad es transitoria, parece causada por la NTI per se, y se resuelve cuando el paciente se recupera. Es común observar una supresión más leve y transitoria de TSH en el rango entre 0,02 y 0,2 mUI/L durante la fase aguda de una enfermedad, seguida de un rebote a valores ligeramente elevados durante la recuperación (103). Es importante utilizar un ensayo de TSH con una sensibilidad funcional ? 0.02 mUI/L en el ambiente hospitalario para estar en condiciones de determinar con seguridad el grado de supresión de TSH. Concretamente, el grado de supresión de TSH se puede utilizar para discriminar a los pacientes hipertiroideos con TSH marcadamente baja (menor a 0,02mUI/L), de los pacientes co una supresión leve y transitoria por NTI (20)

El diagnóstico de hipertiroidismo en los pacientes con enfermedades no tiroideas puede ser un desafío porque los métodos actuales de T4L pueden dar valores inapropiadamente bajos y altos en pacientes eutiroideos con NTI (101, 232). Las determinaciones séricas de T4T y T3T pueden ser útiles para confirmar un diagnóstico de hipertiroidismo si se las analiza en función de la gravedad de la enfermedad (Recomendación Nº 6). Una TSH suprimida por debajo de 0,02 mUI/L es menos específica para el hipertiroidismo en individuos hospitalizados en comparación con los pacientes ambulatorios. Un estudio mostró que el 14% de los pacientes hospitalizados con TSH eutiroideos. No obstante, dichos pacientes tienen una respuesta detectable de la TSH al TRH, mientras que los pacientes verdaderamente hipertiroideos con NTI no la tienen (20).

| Recomendación Nº 6. Ensayos para evaluar la función tiroidea en pacientes hospitalizados con enfermedad no tiroidea (NTI) |

| *Las enfermedades no tiroideas agudas o crónicas tienen efectos complejos sobre los resultados de los ensayos de la función tiroidea. Siempre que sea posible, las pruebas diagnósticas deberían postergarse hasta la resolución de la enfermedad, excepto cuando los antecedentes del paciente o su cuadro clínico sugieran la presencia de disfunción tiroidea. *Los médicos deberían reconocer que ciertos ensayos tiroideos son fundamentalmente no interpretables en pacientes gravemente enfermos o a quienes se están administrando numerosos medicamentos. *La TSH en ausencia de la administración de dopamina o de glucocorticoides, es la determinación más confiable en pacientes con NTI. *Las estimaciones de T4 libre o las determinaciones de T4 total en presencia de una NTI deberían interpretarse con cuidado, y en conjunción con la TSH sérica. Las determinaciones combinadas de + TSH constituyen el modo más confiable de distinguir una verdadera disfunción tiroidea primaria (anormalidades concordantes T4/TSH) de las anormalidades transitorias resultantes de las NTI per se (anormalidades discordantes T4/TSH). *Un ensayo de T4L anormal en presencia de una enfermedad somática severa no es confiable, ya que los métodos de T4L utilizados por los laboratorios clínicos carecen de especificidad diagnóstica para evaluar este tipo de pacientes. *Un resultado de T4L anormal en un paciente hospitalizado se debería confirmar con una T4T «refleja». Es posible que exista patología tiroidea si los valores de T4T y T4L son anormales (en el mismo sentido). Si hay discordancia entre los valores de T4T y T4L, es probable que la anormalidad en la T4L no se deba a una disfunción tiroidea sino que sea consecuencia de la enfermedad, de los medicamentos administrados o de un artefacto del método. *Las anormalidades de T4T deberían ser interpretadas en relación con la severidad de la enfermedad, ya que una T4T baja en presencia de NTI generalmente sólo se ve en pacientes severamente enfermos con una alta tasa de mortalidad. Una T4T baja en un paciente que no está en la unidad de cuidados intensivos indica sospecha de hipotiroidismo. *Un aumento de T3 total o libre es un indicador útil de hipertiroidismo en un paciente hospitalizado, pero una T3 normal o baja no lo descarta. *La determinación de T3 reversa (r-T3) rara vez es útil en el ambiente hospitalario, porque valores paradójicamente normales o bajos pueden resultar de un daño en la función renal o de las concentraciones bajas de proteínas transportadoras. Además, el ensayo no está directamente disponible en la mayoría de los laboratorios. |

No es fácil diagnosticar el hipotiroidismo leve (subclínico) durante la hospitalización, debido a la frecuencia de valores altos de TSH asociados con las NTI. Siempre que la T4L o la T4T estén dentro de los límites normales, es poco probable que una anormalidad menor en la TSH (0,02-20,0 mUI/L) producida por una patología tiroidea leve (subclínica) afecte el resultado de la hospitalización, y se puede posponer la evaluación para 2 o 3 meses después del alta. Por el contrario, los pacientes hipotiroideos enfermos presentan una combinación característica de T4 baja y TSH elevada (>20 mUI/L) (92).

(f) Hipotiroidismo central

La relación logarítmica / lineal entre la TSH y la T4L determina que los pacientes con hipotiroidismo primario y una T4L por debajo de lo normal deberían tener un valor de TSH sérica > 10mUI/L (Figura 1). Cuando el grado de aumento de la TSH asociado con un nivel bajo de hormona tiroidea parece inapropiadamente bajo, se debería descartar insuficiencia hipofisaria. Normalmente no se obtendrá un diagnóstico de hipotiroidismo central si se utiliza la estrategia de TSH como determinación inicial (19).

| Recomendación Nº 26. Tratamiento de reemplazo con levotiroxina (L-T4) para el hipotiroidismo central |

| *El objetivo terapéutico del tratamiento de reemplazo con L-T4 para el hipotiroidismo central debido a disfunción hipofisaria o hipotalámica es una T4L sérica en el tercio superior del intervalo de referencia. *Cuando se utiliza la T4L como punto final terapéutico para el hipotiroidismo central, la dosis diaria de L-T4 debe suprimirse el día de la determinación de T4L. (La T4L sérica aumenta (~13%) por sobre el nivel basal durante 9 horas después de la ingestión de L-T4). |

En la mayoría de los casos, el hipotiroidismo central se caracteriza por valores paradójicamente normales o ligeramente elevados de TSH sérica (29). En un estudio realizado con pacientes con hipotiroidismo central, el 35% de ellos tenía valores de TSH por debajo de lo normal pero el 41% y el 25% tenían valores inapropiadamente normales y elevados, respectivamente (233). En la actualidad existe amplia documentación que demuestra que los niveles paradójicamente elevados de TSH observados en el hipotiroidismo central derivan de la medición de isoformas biológicamente inactivas de TSH secretadas cuando hay daño hipofisario o cuando la estimulación del TRH hipotalámico es deficiente (197). Los valores inapropiados de TSH se deben a que los anticuerpos monoclonales utilizados en los ensayos actuales de TSH no pueden distinguir entre las isoformas de TSH de diferente actividad biológica, ya que la actividad biológica de la TSH está determinada no por la estructura proteica sino por el grado de glucosilación, específicamente la sialización de la molécula. Parecería que una secreción normal de TRH es esencial para la sialización normal de la TSH y para la asociación de las subunidades de TSH para formar moléculas maduras y biológicamente activas (29, 197, 234). La actividad biológica de la TSH en el hipotiroidismo central parece guardar una relación inversa con el grado de sialización de la TSH y con el nivel de T4L en la circulación (29). Las pruebas de estimulación de TRH pueden resultar útiles para el diagnóstico específico del hipotiroidismo central (235). Las respuestas típicas de la TSH en esas condiciones están bloqueadas (aumentos menores al doble del basal/ incrementos ? 4.0 mUI/L) y el pico puede estar demorado (197, 204, 235, 236). Además, la respuesta de T3 a la TSH estimulada por TRH está bloqueada y se correlaciona con la actividad biológica de la TSH (197, 237, 238).

(g) Síndromes de secreción,inapropiada de TSH

Como se muestra en la Tabla 1, las anormalidades de las proteínas transportadoras o los problemas técnicos de los ensayos son las causas más comunes de una relación T4L/TSH discordante. La disociación aparentemente paradójica entre los niveles altos de hormonas tiroideas y una TSH sérica no suprimida ha llevado al uso generalizado del término “síndrome de secreción inapropiada de TSH” para describir estas patologías. Cada vez más están siendo identificadas muestras que presentan una relación TSH/T4L discordante, dada la disponibilidad y uso generalizados de ensayos de TSH sensibles, que pueden detectar en forma confiable concentraciones de TSH subnormales. Como se muestra en la Tabla 1, es fundamental descartar primero las causas probables de una discordancia en el índice TSH/T4L (por ejemplo, interferencia técnica o anormalidades en las proteínas transportadoras). Esta confirmación se debería realizar sobre una nueva muestra determinando TSH junto con las hormonas tiroideas libres y totales, con el método de otro fabricante. Patologías menos frecuentes, como tumores hipofisarios secretantes de TSH o resistencia a las hormonas tiroideas sólo deberían considerarse después de eliminar las causas más comunes de discordancia.

Una vez confirmada la anormalidad en el perfil bioquímico, se debería descartar primero la posibilidad de que un tumor hipofisario secretante de TSH sea la causa de los valores paradójicos de TSH antes de efectuar el diagnóstico de resistencia a las hormonas tiroideas. Cabe observar que es posible la coexistencia de ambas patologías (247). Los tumores hipofisarios secretantes de TSH tienen perfiles bioquímicos similares a la resistencia a las hormonas tiroideas pero se los puede distinguir de éstas mediante la determinación de subunidad alfa de TSH y diagnóstico por imágenes. Además, las pruebas de estimulación con TRH pueden ser ocasionalmente útiles para desarrollar el diagnóstico diferencial.

Concretamente, una prueba de estimulación de TRH y una prueba de supresión de T3 con respuesta bloqueada son características de la mayoría de los tumores hipofisarios secretantes de TSH, mientras que en la mayoría de los casos de resistencia a las hormonas tiroideas se observa una respuesta normal (245).

| Recomendación Nº 27. Utilidad clínica de los ensayos de TSH (Sensibilidad funcional ? 0,02 mUI/L) |

| *La determinación de TSH sérica es el ensayo más sensible para la detección de hipo o hipertiroidismo primario leve (subclínico) y clínico en los pacientes ambulatorios. *La mayoría (>95%) de los individuos sanos eutiroideos tiene una concentración de TSH sérica por debajo de 2,5 mUI/L. Los pacientes ambulatorios con TSH sérica por encima de 2,5 mUI/L confirmada por una segunda determinación realizada entre 3 y 4 semanas después, pueden hallarse en las primeras etapas de disfunción tiroidea, en particular si se detectan TPOAb. *La determinación de TSH sérica es el punto final terapéutico para el ajuste de dosis de reemplazo con L-T4 para el hipotiroidismo primario (ver Recomendación Nº 23) y para controlar el tratamiento de supresión con L-T4 para el carcinoma diferenciado de tiroides (ver Recomendación Nº 24). Las determinaciones de TSH sérica son más confiables que las de T4L en pacientes hospitalizados con enfermedades no tiroideas que no reciban dopamina. La TSH sérica se debería utilizar junto con la T4T o T4L para los pacientes hospitalizados (Recomendación Nº 6 y 26). *La TSH no se puede utilizar para diagnosticar hipotiroidismo central porque los ensayos actuales de TSH miden isoformas biológicamente inactivas de TSH. *El hipotiroidismo central se caracteriza por un nivel inapropiadamente normal o ligeramente elevado de TSH sérica y una respuesta nula al TRH (aumentos *Debería ser considerado un diagnóstico de hipotiroidismo central en caso de disminución de T4L y mínima elevación de la TSH sérica ( *Las determinaciones de TSH son una importante prueba de screening pre-natal y en el primer trimestre de embarazo para detectar hipotiroidismo leve (subclínico) en la madre (ver Recomendación Nº 4). *Una TSH baja en un bocio multinodular sugiere hipertiroidismo leve (subclínico) debido a autonomía tiroidea. Se requiere una determinación de TSH para confirmar que un nivel de hormona tiroidea alto se debe a hipertiroidismo y no a una anormalidad en las proteínas transportadoras como en l a hipertiroxinemia disalbuminémica familiar (FDH). *La TSH sérica es la determinación primaria para la detección de disfunción tiroidea inducida por amiodarona (ver Recomendación Nº5). |

(i) Tumores hipofisarios secretantes de TSH

Los tumores hipofisarios que hiper-secretan TSH no son frecuentes y representan menos del 1% de los casos de secreción inapropiada de TSH (27, 28). Estos tumores a menudo se presentan como un macroadenoma con síntomas de hipertiroidismo, asociado a TSH no suprimida y evidencia mediante resonancia magnética (MRI), de masa hipofisaria (28).

Después de descartar una razón técnica para la elevación paradójica de TSH (por ejemplo anticuerpos heterófilos HAMA), el diagnóstico de tumor hipofisario secretante de TSH

generalmente se realiza sobre la base de:

- Falta de respuesta de la TSH al TRH

- Una subunidad alfa de TSH alta

- Una relación subunidad alfa/TSH aumentada

- La demostración de una masa hipofisaria mediante resonancia magnética.

| Recomendación Nº 28. Para los fabricantes de equipos de reactivos de TSH |

| *Es necesario que los fabricantes que comercializan los reactivos para determinación de TSH con diversas sensibilidades interrumpan la comercialización del producto menos sensible. *No se justifica que el precio de los ensayos de TSH se establezca en función de la sensibilidad. No existe justificación científica para realizar primero un ensayo de TSH menos sensible y luego pasar a otro más sensible. *Los fabricantes deberían ayudar a que los laboratorios puedan establecer la sensibilidad funcional independientemente de ellos, suministrándoles mezclas de suero humano con TSH adecuadamente baja cuando se les solicite. *Los fabricantes deberían indicar el uso de factores de calibración, en especial si estos factores dependen de cada país. *Los fabricantes deberían citar el porcentaje de recuperación de la preparación de referencia de TSH a la concentración indicada como sensibilidad funcional. *Los folletos con los procedimientos técnicos dentro de la caja del equipo deberían: 54 Dic 2011 Diagnóstico Clínico Aplicado – Documentar la sensibilidad funcional real de los métodos utilizando el protocolo de la Recomendación N° 20. – Citar la sensibilidad funcional que se puede alcanzar a través de un rango de laboratorios clínicos utilizando el mismo equipo de reactivos. – Mostrar el perfil de precisión interensayo típico que se espera de un laboratorio clínico. – Recomendar el uso de sensibilidad funcional y no analítica para determinar el valor más bajo reportable. (La sensibilidad analítica insta a los laboratorios a que adopten límites de detección no reales). |

(ii) Resistencia a las hormonas tiroideas

Generalmente, la resistencia a las hormonas tiroideas es provocada por una mutación en el gen del receptor de las hormonas tiroideas (TRbeta), que ocurre en 1:50.000 nacimientos vivos (239-242). Aunque la presentación clínica puede variar, los pacientes tienen un perfil bioquímico similar. La T4L y la T3L están típicamente elevadas (desde un grado mínimo hasta duplicar o triplicar el valor por sobre el límite normal superior) y se asocian con una TSH normal o ligeramente elevada que responde a la estimulación con TRH (242, 243). Sin embargo, se debería reconocer que la secreción de TSH no es inapropiada ya que se reduce la respuesta de los tejidos a la hormona tiroidea y en consecuencia se requieren niveles más altos de hormonas tiroideas para mantener el estado metabólico normal. Los pacientes con resistencia a las hormonas tiroideas suelen tener bocio como resultado de la hipersecreción crónica de una isoforma de TSH híbrida con mayor actividad biológica (199, 244). La manifestación clínica del exceso de la hormona tiroidea cubre un amplio espectro.

Algunos pacientes parecen tener un metabolismo normal con valores casi normales de TSH y en ellos el defecto del receptor parece estar compensado por un aumento en los niveles de la hormona tiroidea (resistencia generalizada a las hormonas tiroideas). Otros pacientes parecen ser hiper-metabólicos y tienen un defecto que afecta selectivamente a la hipófisis (resistencia hipofisaria a la hormona tiroidea).

Los rasgos distintivos de la resistencia a las hormonas tiroideas son la presencia de una TSH no suprimida junto con una respuesta adecuada al TRH a pesar del aumento en los niveles de hormonas tiroideas (242, 245). Aunque no sea frecuente, es importante que se considere el diagnóstico de resistencia a las hormonas tiroideas al encontrar un paciente con aumento en los niveles de estas hormonas asociado con un nivel paradójicamente normal o elevado de TSH (242, 246). A menudo esos pacientes han recibido un diagnóstico erróneo de hipertiroidismo y se los ha sometido a una cirugía tiroidea innecesaria o a la ablación de la glándula con radioyodo (242).

Referencias Bibliográficas

1. Nohr SB, Laurberg P, Borlum KG, Pedersen Km, Johannesen PL, Damm P. Iodine deficiency in pregnancy in Denmark. Regional variations and frequency of individual iodine supplementation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1993;72:350-3.

2. Glinoer D. Pregnancy and iodine. Thyroid 2001;11:471-81.

3. Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Hannon WH, Flanders DW, Gunter EW, Maberly GF et al. Iodine nutrition in the Unites States. Trends and public health implications: iodine excretion data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys I and III (1971-1974 and 1988-1994). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:3398-400.

4. Wartofsky L, Glinoer D, Solomon d, Nagataki S, Lagasse R, Nagayama Y et al. Differences and similarities in the diagnosis and treatment of Graves disease in Europe, Japan and the United States. Thyroid 1990;1:129-35.

5. Singer PA, Cooper DS, Levy EG, Ladenson PW, Braverman LE, Daniels G et al. Treatment guidelines for patients with hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. JAMA 1995;273:808-12.

6. Singer PA, Cooper DS, Daniels GH, Ladenson PW, Greenspan FS, Levy EG et al. Treatment Guidelines for Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Well-differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:2165-72.

7. Vanderpump MPJ, Ahlquist JAO, Franklyn JA and Clayton RN. Consensus statement for good practice and audit measures in the management of hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. Br Med J 1996;313:539-44.

8. Laurberg P, Nygaard B, Glinoer D, Grussendorf M and Orgiazzi J. Guidelines for TSH-receptor antibody measurements in pregnancy: results of an evidence-based symposium organized by the European Thyroid Association. Eur J Endocrinol 1998;139:584-6.

9. Cobin RH, Gharib H, Bergman DA, Clark OH, Cooper DS, Daniels GH et al. AACE/AAES Medical/Surgical Guidelines for Clinical Practice: Management of Thyroid Carcinoma. Endocrine Pract 2001;7:203-20.

10. Ladenson PW, Singer PA, Ain KB, Bagchi N, Bigos ST, Levy EG et al. American Thyroid Association Guidelines for detection of thyroid dysfunction. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1573-5.

11. Brandi ML, Gagel RJ, Angeli A, Bilezikian JP, Beck-Peccoz P, Bordi C et al. Consensus Guidelines for Diagnosis and Therapy of MEN Type 1 and Type 2. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:5658-71.

12. Werner and Ingbar’s “The Thyroid”. A Fundamental and Clinical Text. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia 2000. Braverman LE and Utiger RD eds.

13. DeGroot LJ, Larsen PR, Hennemann G, eds. The Thyroid and Its Diseases. (www.thyroidmanager.org) 2000.

14. Piketty ML, D’Herbomez M, Le Guillouzic D, Lebtahi R, Cosson E, Dumont A et al. Clinical comparison of three labeled-antibody immunoassays of free triiodothyronine. Clin Chem 1996;42:933-41.

15. Sapin R, Schlienger JL, Goichot B, Gasser F and Grucker D. Evaluation of the Elecsys free triiodothyronine assay; relevance of age-related reference ranges. Clin Biochem 1998;31:399-404.

16. Robbins J. Thyroid hormone transport proteins and the physiology of hormone binding. In “Hormones in Blood”. Academic Press, London 1996. Gray CH, James VHT, eds. pp 96-110.

17. Demers LM. Thyroid function testing and automation. J Clin Ligand Assay 1999;22:38-41.

18. Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Hannon WH, Flanders WD, Gunter EW, Spencer CA et al. Serum thyrotropin, thyroxine and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): NHANES III. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:489-99.

19. Wardle CA, Fraser WD and Squire CR. Pitfalls in the use of thyrotropin concentration as a first-line thyroid-function test. Lancet 2001;357:1013-4.

20. Spencer CA, LoPresti JS, Patel A, Guttler RB, Eigen A, Shen D et al. Applications of a new chemiluminometric thyrotropin assay to subnormal measurement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1990;70:453-60.

21. Meikle, A. W., J. D. Stringham, M. G. Woodward and J. C. Nelson. Hereditary and environmental influences on the variation of thyroid hormones in normal male twins. J Clin Endocrinol Metab1 1988;66:588-92.

22. Andersen S, Pedersen KM, Bruun NH and Laurberg P. Narrow individual variations in serum T4 and T3 in normal subjects: a clue to the understanding of subclinical thyroid disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:1068-72.

23. Cooper, D. S., R. Halpern, L. C. Wood, A. A. Levin and E. V. Ridgway. L-thyroxine therapy in subclinical hypothyroidism. Ann Intern Med 1984;101:18-24.

24. Biondi B, Fazio E, Palmieri EA, Carella C, Panza N, Cittadini A et al. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;2064-7.

25. Hak AE, Pols HAP, Visser TJ, Drexhage HA, Hofman A and Witteman JCM. Subclinical Hypothyroidism is an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction in elderly women: the Rotterdam Study. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:270-8.

26. Michalopoulou G, Alevizaki M, Piperingos G, Mitsibounas D, Mantzos E, Adamopoulos P et al. High serum cholesterol levels in persons with ‘high-normal’ TSH levels: should one extend the definition of subclinical hypothyroidism? Eur J Endocrinol 1998;138:141-5.

27. Beck-Peccoz P, Brucker-Davis F, Persani L, Smallridge RC and Weintraub BD. Thyrotropin-secreting pituitary tumors. Endocrine Rev 1996;17:610-38.

28. Brucker-Davis F, Oldfield EH, Skarulis MC, Doppman JL and Weintraub BD. Thyrotropin-secreting pituitary tumors: diagnostic criteria, thyroid hormone sensitivity and treatment outcome in 25 patients followed at the National Institutes of Health. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 76 1999;:1089-94.

29. Oliveira JH, Persani L, Beck-Peccoz P and Abucham J. Investigating the paradox of hypothyroidism and increased serum thyrotropin (TSH) levels in Sheehan’s syndrome: characterization of TSH carbohydrate content and bioactivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:1694-9.

30. Uy H, Reasner CA and Samuels MH. Pattern of recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary thyroid axis following radioactive iodine therapy in patients with Graves’ disease. Amer J Med 1995;99:173-9.

31. Hershman JM, Pekary AE, Berg L, Solomon DH and Sawin CT. Serum thyrotropin and thyroid hormone levels in elderly and middle-aged euthyroid persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993;41:823-8.

32. Fraser CG. Age-related changes in laboratory test results. Clinical applications. Drugs Aging 1993;3:246-57.

33. Fraser CG. 2001. Biological Variation: from principles to practice. AACC Press, Washington DC.

34. Drinka PJ, Siebers M and Voeks SK. Poor positive predictive value of low sensitive thyrotropin assay levels for hyperthyroidism in nursing home residents. South Med J 1993;86:1004-7.

35. Vanderpump MPJ, Tunbridge WMG, French JM, Appleton D, Bates D, Rodgers H et al. The incidence of thyroid disorders in the community; a twenty year follow up of the Whickham survey. Clin Endocrinol 1995;43:55-68.

36. Sawin CT, Geller A, Kaplan MM, Bacharach P, Wilson PW, Hershman JM et al. Low serum thyrotropin (thyroid stimulating hormone) in older persons without hyperthyroidism. Arch Intern Med 1991;151:165-8.

37. Parle JV, Maisonneuve P, Sheppard MC, Boyle P and Franklyn JA. Prediction of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in elderly people from one low serum thyrotropin result: a 10-year study. Lancet 2001;358:861-5.

38. Nelson JC, Clark SJ, Borut DL, Tomei RT and Carlton EI. Age-related changes in serum free thyroxine during childhood and adolescence. J Pediatr 1993;123:899-905.

39. Adams LM, Emery JR, Clark SJ, Carlton EI and Nelson JC. Reference ranges for newer thyroid function tests in premature infants. J Pediatr 1995;126:122-7.

40. Lu FL, Yau KI, Tsai KS, Tang JR, Tsao PN and Tsai WY. Longitudinal study of serum free thyroxine and thyrotropin levels by chemiluminescent immunoassay during infancy. T’aiwan Erh K’o i Hseh Hui Tsa Chih 1999;40:255-7.

41. Zurakowski D, Di Canzio J and Majzoub JA. Pediatric reference intervals for serum thyroxine, triiodothyronine, thyrotropin and free thyroxine. Clin Chem 1999;45:1087-91.

42. Fisher DA, Nelson JC, Carlton Ei and Wilcox RB. Maturation of human hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid function and control. Thyroid 2000;10:229-34.

43. Fisher DA, Schoen EJ, La Franchi S, Mandel SH, Nelson JC, Carlton EI and Goshi JH. The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid negative feedback control axis in children with treated congenital hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:2722-7.

44. Penny R, Spencer CA, Frasier SD and Nicoloff JT. Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and thyroglobulin (Tg) levels decrease with chronological age in children and adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1983;56:177-80.

45. Verheecke P. Free triiodothyronine concentration in serum of 1050 euthyroid children is inversely related to their age. Clin Chem 1997;43:963-7.

46. Glinoer D, De Nayer P, Bourdoux P, Lemone M, Robyn C, van Steirteghem A et al. Regulation of maternal thyroid function during pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1990;71:276-87.

47. Glinoer D. The regulation of thyroid function in pregnancy: pathways of endocrine adaptation from physiology to pathology. Endocrinol Rev 1997;18:404-33.

48. Weeke J, Dybkjaer L, Granlie K, Eskjaer Jensen S, Kjaerulff E, Laurberg P et al. A longitudinal study of serum TSH and total and free iodothyronines during normal pregnancy. Acta Endocrinol 1982;101:531-7.

49. Pedersen KM, Laurberg P, Iversen E, Knudsen PR, Gregersen HE, Rasmussen OS et al. Amelioration of some pregnancy associated variation in thyroid function by iodine supplementation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1993;77:1078-83.

50. Nohr SB, Jorgensen A, Pedersen KM and Laurberg P. Postpartum thyroid dysfunction in pregnant thyroid peroxidase antibody-positive women living in an area with mild to moderate iodine deficiency: Is iodine supplementation safe? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:3191-8.

51. Panesar NS, Li CY and Rogers MS. Reference intervals for thyroid hormones in pregnant Chinese women. Ann Clin Biochem 2001;38:329-32.

52. Nissim M, Giorda G, Ballabio M, D’Alberton A, Bochicchio D, Orefice R et al. Maternal thyroid function in early and late pregnancy. Horm Res 1991;36:196-202.

53. Talbot JA, Lambert A, Anobile CJ, McLoughlin JD, Price A, Weetman AP et al. The nature of human chorionic gonadotrophin glycoforms in gestational thyrotoxicosis. Clin Endocrinol 2001;55:33-9.

54. Jordan V, Grebe SK, Cooke RR, Ford HC, Larsen PD, Stone PR et al. Acidic isoforms of chorionic gonadotrophin in European and Samoan women are associated with hyperemesis gravidarum and may be thyrotrophic. Clin Endocrinol 1999;50:619-27.

55. Goodwin TM, Montoro M, Mestman JH, Pekary AE and Hershman JM. The role of chorionic gonadotropin in transient hyperthyroidism of hyperemesis gravidarum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1992;75:1333-7.

56. Hershman JM. Human chorionic gonadotropin and the thyroid: hyperemesis gravidarum and trophoblastic tumors. Thyroid 1999;9:653-7.

57. McElduff A. Measurement of free thyroxine (T4) in pregnancy. Aust NZ J Obst Gynecol 1999;39:158-61.

58. Christofides, N., Wilkinson E, Stoddart M, Ray DC and Beckett GJ. Assessment of serum thyroxine binding capacity-dependent biases in free thyroxine assays. Clin Chem 1999;45:520-5.

59. Roti E, Gardini E, Minelli R, Bianconi L, Flisi M,. Thyroid function evaluation by different commercially available free thyroid hormone measurement kits in term pregnant women and their newborns. J Endocrinol Invest 1991;14:1-9.

60. Stockigt JR. Free thyroid hormone measurement: a critical appraisal. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am 2001;30:265-89.

61. Mandel SJ, Larsen PR, Seely EW and Brent GA. Increased need for thyroxine during pregnancy in women with primary hypothyroidism. NEJM 1990;323:91-6.

62. Burrow GN, Fisher DA and Larsen PR. Maternal and fetal thyroid function. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1072-8.

63. Pop VJ, De Vries E, Van Baar AL, Waelkens JJ, De Rooy HA, Horsten M et al. Maternal thyroid peroxidase antibodies during pregnancy: a marker of impaired child development? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995;80:3561-6.

64. Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Allan WC, K. G. Williams JR, Gagnon J, O’Heir CE et al. Maternal thyroid deficiency during pregnancy and subsequent neuropsychological development of the child. NEJM 1999;341:549-55.

65. Pop VJ, Kuijpens JL, van Baar AL, Verkerk G, van Son MM, de Vijlder JJ et al. Low maternal free thyroxine concentrations during early pregnancy are associated with impaired psychomotor development in infancy. Clin Endocrinol 1999;50:147-8.

66. Radetti G, Gentili L, Paganini C, Oberhofer R, Deluggi I and Delucca A. Psychomotor and audiological assessment of infants born to mothers with subclinical thyroid dysfunction in early pregnancy. Minerva Pediatr 2000;52:691-8.

67. Surks MI and Sievert R. Drugs and thyroid function. NEJM 1995;333:1688-94.

68. Kailajarvi M, Takala T, Gronroos P, Tryding N, Viikari J, Irjala K et al. Reminders of drug effects on laboratory test results. Clin Chem 2000;46:1395-1400.

69. Brabant A, Brabant G, Schuermeyer T, Ranft U, Schmidt FW, Hesch RD et al. The role of glucocorticoids in the regulation of thyrotropin. Acta Endocrinol 1989;121:95-100.

70. Samuels MH and McDaniel PA. Thyrotropin levels during hydrocortisone infusions that mimic fasting-induced cortisol elevations: a clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:3700-4.

71. Kaptein EM, Spencer CA, Kamiel MB and Nicoloff JT. Prolonged dopamine administration and thyroid hormone economy in normal and critically ill subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1980;51:387-93.

72. Geffner DL and Hershman JM. Beta-adrenergic blockade for the treatment of hyperthyroidism. Am J Med 1992;93:61-8.

73. Meurisse M, Gollogly MM, Degauque C, Fumal I, Defechereux T and Hamoir E. Iatrogenic thyrotoxicosis: causal circumstances, pathophysiology and principles of treatment- review of the literature. World J Surg 2000;24:1377-85.

74. Martino E, Aghini-Lombardi F, Mariotti S, Bartelena L, Braverman LE and Pinchera A. Amiodarone: a common source of iodine-induced thyrotoxicosis. Horm Res 1987;26:158-71.

75. Martino E, Bartalena L, Bogazzi F and Braverman LE. The effects of amiodarone on the Thyroid. Endoc Rev 2001;22:240-54.

76. Daniels GH. Amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:3-8.

77. Harjai KJ and Licata AA. Effects of amiodarone on thyroid function. Ann Intern Med 1997;126:63-73.

78. Caron P. Effect of amiodarone on thyroid function. Press Med 1995;24:1747-51.

79. Bartalena L, Grasso L, Brogioni S, Aghini-Lombardi F, Braverman LE and Martino E. Serum interleukin-6 in amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994;78:423-7.

80. Eaton SE, Euinton HA, Newman CM, Weetman AP and Bennet WM. Clinical experience of amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis over a 3-year period: role of colour-flow Doppler sonography. Clin Endocrinol 2002;56:33-8.

81. Lazarus JH. The effects of lithium therapy on thyroid and thyrotropin-releasing hormone. Thyroid 1998;8:909-13.

82. Kusalic M and Engelsmann F. Effect of lithium maintenance therapy on thyroid and parathyroid function. J Psych Neurosci 1999;24:227-33.

83. Oakley PW, Dawson AH and Whyte IM. Lithium: thyroid effects and altered renal handling. Clin Toxicol 2000;38:333-7.

84. Mendel CM, Frost PH, Kunitake ST and Cavalieri RR. Mechanism of the heparin-induced increase in the concentration of free thyroxine in plasma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1987;65:1259-64.

85. Iitaka M, Kawasaki S, Sakurai S, Hara Y, Kuriyama R, Yamanaka K et al. Serum substances that interfere with thyroid hormone assays in patients with chronic renal failure. Clin Endocrinol 1998;48:739-46.

86. Bowie LJ, Kirkpatrick PB and Dohnal JC. Thyroid function testing with the TDx: Interference from endogenous fluorophore. Clin Chem 1987;33:1467.

87. DeGroot LJ and Mayor G. Admission screening by thyroid function tests in an acute general care teaching hospital. Amer J Med 1992;93:558-64.

88. Kaptein EM. Thyroid hormone metabolism and thyroid diseases in chronic renal failure. Endocr Rev 1996;17:45-63.

89. Van den Berghe G, De Zegher F and Bouillon R. Acute and prolonged critical illness as different neuroendocrine paradigms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:1827-34.

90. Van den Berhe G. Novel insights into the neuroendocrinology of critical illness. Eur J Endocrinol 2000;143:1-13.

91. Wartofsky L and Burman KD. Alterations in thyroid function in patients with systemic illness: the “euthyroid sick syndrome”. Endocrinol Rev 1982;3:164-217.

92. Spencer CA, Eigen A, Duda M, Shen D, Qualls S, Weiss S et al. Sensitive TSH tests – specificity limitations for screening for thyroid disease in hospitalized patients. Clin Chem 1987;33:1391-1396.

93. Stockigt JR. Guidelines for diagnosis and monitoring of thyroid disease: nonthyroidal illness. Clin Chem 1996;42:188-92.

94. Nelson JC and Weiss RM. The effects of serum dilution on free thyroxine (T4) concentration in the low T4 syndrome of nonthyroidal illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1985;61:239-46.

95. Chopra IJ, Huang TS, Beredo A, Solomon DH, Chua Teco GN. Serum thyroid hormone binding inhibitor in non thyroidal illnesses. Metabolism 1986;35:152-9.

96. Wang R, Nelson JC and Wilcox RB. Salsalate administration – a potential pharmacological model of the sick euthyroid syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:3095-9.

97. Sapin R, Schliener JL, Kaltenbach G, Gasser F, Christofides N, Roul G et al. Determination of free triiodothyronine by six different methods in patients with non-thyroidal illness and in patients treated with amiodarone. Ann Clin Biochem 1995;32:314-24.

98. Docter R, van Toor H, Krenning EP, de Jong M and Hennemann G. Free thyroxine assessed with three assays in sera of patients with nonthyroidal illness and of subjects with abnormal concentrations of thyroxine-binding proteins. Clin Chem 1993;39:1668-74.

99. Wilcox RB, Nelson JC and Tomei RT. Heterogeneity in affinities of serum proteins for thyroxine among patients with non-thyroidal illness as indicated by the serum free thyroxine response to serum dilution. Eur J Endocrinol 1994;131:9-13.

100. Liewendahl K, Tikanoja S, Mahonen H, Helenius T, Valimaki M and Tallgren LG. Concentrations of iodothyronines in serum of patients with chronic renal failure and other nonthyroidal illnesses: role of free fatty acids. Clin Chem 1987;33:1382-6.

101. Sapin R, Schlienger JL,Gasser F, Noel E, Lioure B, Grunenberger F. Intermethod discordant free thyroxine measurements in bone marrow-transplanted patients. Clin Chem 2000;46:418-22.

102. Chopra IJ. Simultaneous measurement of free thyroxine and free 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine in undiluted serum by direct equilibrium dialysis/radioimmunoassay: evidence that free triiodothyronine and free thyroxine are normal in many patients with the low triiodothyronine syndrome. Thyroid 1998;8:249-57.

103. Hamblin PS, Dyer SA, Mohr VS, Le Grand BA, Lim C-F, Tuxen DB, Topliss DJ and Stockigt JR. Relationship between thyrotropin and thyroxine changes during recovery from severe hypothyroxinemia of critical illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1986;62:717-22.

104. Brent GA and Hershman JM. Thyroxine therapy in patients with severe nonthyroidal illnesses and low serum thyroxine concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1986;63:1-8.

105. De Groot LJ. Dangerous dogmas in medicine: the nonthyroidal illness syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:151-64.

106. Burman KD and Wartofsky L. Thyroid function in the intensive care unit setting. Crit Care Clin 2001;17:43-57.

107. Behrend EN, Kemppainen RJ and Young DW. Effect of storage conditions on cortisol, total thyroxine and free thyroxine concentrations in serum and plasma of dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998;212:1564-8.

108. Oddie TH, Klein AH, Foley TP and Fisher DA. Variation in values for iodothyronine hormones, thyrotropin and thyroxine binding globulin in normal umbilical-cord serum with season and duration of storage. Clin Chem 1979;25:1251-3.

109. Koliakos G, Gaitatzi M and Grammaticos P. Stability of serum TSH concentration after non refrigerated storage. Minerva Endocrinol 1999;24:113-5.

110. Waite KV, Maberly GF and Eastman CJ. Storage conditions and stability of thyrotropin and thyroid hormones on filter paper. Clin Chem 1987;33:853-5.

111. Levinson SS. The nature of heterophilic antibodies and their role in immunoassay interference. J Clin Immunoassay 1992;15:108-15.

112. Norden AGM, Jackson RA, Norden LE, Griffin AJ, Barnes MA and Little JA. Misleading results for immunoassays of serum free thyroxine in the presence of rheumatoid factor. Clin Chem 1997;43:957-62.

113. Covinsky M, Laterza O, Pfeifer JD, Farkas-Szallasi T and Scott MG. Lambda antibody to Esherichia coli produces false-positive results in multiple immunometric assays. Clin Chem 2000;46:1157-61.

114. Martel J, Despres N, Ahnadi CE, Lachance JF, Monticello JE, Fink G, Ardemagni A, Banfi G, Tovey J, Dykes P, John R, Jeffery J and Grant AM. Comparative multicentre study of a panel of thyroid tests using different automated immunoassay platforms and specimens at high risk of antibody interference. Clin Chem Lab Med 2000;38:785-93.

115. Howanitz PJ, Howanitz JH, Lamberson HV and Ennis KM. Incidence and mechanism of spurious increases in serum Thyrotropin. Clin Chem 1982;28:427-31.

116. Boscato, L. M. and M. C. Stuart. Heterophilic antibodies: a problem for all immunoassays. Clin Chem 1988;34:27-33.

117. Kricka LJ. Human anti-animal antibody interference in immunological assays. Clin Chem 1999;45:942-56.

118. Sapin R and Simon C. False hyperprolactinemia corrected by the use of heterophilic antibody-blocking agent. Clin Chem 2001;47:2184-5.

119. Feldt-Rasmussen U, Petersen PH, Blaabjerg O and Horder M. Long-term variability in serum thyroglobulin and thyroid related hormones in healthy subjects. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1980;95:328-34.

120. Browning MCK, Ford RP, Callaghan SJ and Fraser CG. Intra-and interindividual biological variation of five analytes used in assessing thyroid function: implications for necessary standards of performance and the interpretation of results. Clin Chem 1986;32:962-6.

121. Lum SM and Nicoloff JT. Peripheral tissue mechanism for maintenance of serum triiodothyronine values in a thyroxine-deficient state in man. J Clin Invest 1984;73:570-5.

122. Spencer CA and Wang CC. Thyroglobulin measurement:- Techniques, clinical benefits and pitfalls. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Amer 1995;24:841-63.

123. Weeke J and Gundersen HJ. Circadian and 30 minute variations in serum TSH and thyroid hormones in normal subjects. Acta Endocrinol 1978;89:659-72.

124. Brabant G, Prank K, Hoang-Vu C and von zur Muhlen A. Hypothalamic regulation of pulsatile thyrotropin secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991;72:145-50.

125. Fraser CG, Petersen PH, Ricos C and Haeckel R. Proposed quality specifications for the imprecision and inaccuracy of analytical systems for clinical chemistry. Eur J Clin Chem Biochem 1992;30:311-7.

126. Rodbard, D. Statistical estimation of the minimal detectable concentration (“sensitivity”) for radioligand assays. Anal Biochem 1978;90:1-12.

127. Ekins R and Edwards P. On the meaning of “sensitivity”. Clin Chem 1997;43:1824-31.

128. Fuentes-Arderiu X and Fraser CG. Analytical goals for interference. Ann Clin Biochem 1991;28:393-5.

129. Petersen PH, Fraser CG, Westgard JO and Larsen ML. Analytical goal-setting for monitoring patients when two analytical methods are used. Clin Chem 1992;38:2256-60.

130. Fraser CG and Petersen PH. Desirable standards for laboratory tests if they are to fulfill medical needs. Clin Chem 1993;39:1453-5.

131. Stockl D, Baadenhuijsen H, Fraser CG, Libeer JC, Petersen PH and Ricos C. Desirable routine analytical goals for quantities assayed in serum. Discussion paper from the members of the external quality assessment (EQA) Working Group A on analytical goals in laboratory medicine. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem 1995;33:157-69.

132. Plebani M, Giacomini A, Beghi L, de Paoli M, Roveroni G, Galeotti F, Corsini A and Fraser CG. Serum tumor markers in monitoring patients: interpretation of results using analytical and biological variation. Anticancer Res 1996;16:2249-52.

133. Browning MC, Bennet WM, Kirkaldy AJ and Jung RT. Intra-individual variation of thyroxin, triiodothyronine and thyrotropin in treated hypothyroid patients: implications for monitoring replacement therapy. Clin Chem 1988;34:696-9.

134. Harris EK. Statistical principles underlying analytic goal-setting in clinical chemistry. Am J Clin Pathol 1979;72:374-82.

135. Nelson JC and Wilcox RB. Analytical performance of free and total thyroxine assays. Clin Chem 1996;42:146-54.

136. Evans SE, Burr WA and Hogan TC. A reassessment of 8-anilino-1-napthalene sulphonic acid as a thyroxine binding inhibitor in the radioimmunoassay of thyroxine. Ann Clin Biochem 1977;14:330-4.

137. Karapitta CD, Sotiroudis TG, Papadimitriou A and Xenakis A. Homogeneous enzyme immunoassay for triiodothyronine in serum. Clin Chem 2001;47:569-74.

138. De Brabandere VI, Hou P, Stockl D, Theinpont LM and De Leenheer AP. Isotope dilution-liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry for the determination of serum thyroxine as a potential reference method. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 1998;12:1099-103.

139. Tai SSC, Sniegoski LT and Welch MJ. Candidate reference method for total thyroxine in human serum: Use of isotope-dilution liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry with electrospray ionization. Clin Chem 2002;48:637-42.